"A Mountain Peace" By Julie L. Semrau, Reprinted from Yippy Yi Yea Magazine, Fall 1994

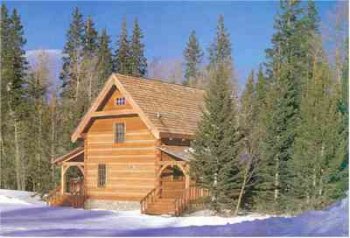

A winding private road climbs up the side of a mountain overlooking scenic vistas of Wheeler and Taos mountains in the distance. Michael's cabin, banked by sheltering pines on one side, glows with sunlight on the natural wood of its walls. Its modest fieldstone chimney is outlined by the brilliant blue of the New Mexico sky.

Inside the cabin, a collection of mementos and practical necessities reveals as much about the surrounding wildlife as a tour guide. The wool curtains and vintage china in the kitchen are the color of fresh pine needles-green, an Irishman's favorite color and the color of the forest. Carvings of birds and animals, most native to the surrounding mountains, are arranged on the tops of tables and shelves. Many gifts from friends include beaded leather gloves used in Native American church ceremonies and a plaque from a mountain main at WestFest. Ask about anything in the cabin, and a common refrain runs through Michael's response: if it's here, it's here for a reason.

"The china I picked out is the same that my grandmother had, and I have really fond memories of it," he says walking into the kitchen. The full set of dishes, "Curiosity Shop," is a New England design that dates from the '40s and '50s. Years ago, Michael saw one of the plates in a store window and immediately remembered his grandmother's set. He collected a full set of the green and white china just for the cabin. Other touches seem to soften the wild, mountain man feel of the cabin as well. His maternal grandmother loved roses, an inclination shared by his wife. A cotton throw, his grandmother's lamp and a Victorian print all are reminiscent of this grandmother's influence. "There's a lot of tradition from the women in my family here," he says. "I wanted my wife, Mary, to be comfortable here, but comfortable through my eyes."

An obvious pride in his Irish heritage is evident inside this cabin. "The Irish towels were given to me by my grandfather when he first went to search out the family. He kissed the Blarney stone, and he bought the towels in the gift shop by the castle where the Blarney stone is. He gave those to me when I was about 10 or 11 years old," says Michael. His intent wasn't merely to make a place to store a trove of ancestral treasures - it welcomes the presence of his children in many ways. The cabin gives equal time to all of Michael's family: past, present and future. Twin beds in the loft overlooking the sitting room are filled with the tools of modern childhood: books, drawings, dolls and the like; but no television, telephone or computer games. "It actually takes two to three days for them to get into the feeling of it," Michael says of his two younger children. "They'll get out into the woods and just play all day, build forts and whatever. That's the way I grew up, and I want them to feel that. My grandmother and my grandfather gave me that gift, and it's a gift that stuck with me. I wanted them to feel the feeling of being out in the country, or on a farm or up in the mountains. That's why we really moved here, and I wasn't about to let that stop at the front door. I want it to be inside as well, because when I grew up in those old farmhouses, the atmosphere inside was just as wonderful as it was outside."

Michael's main goal for the cabin, a place to write, has obvious influences on the cabin's interior. His desk, without computer, phone or fax, is exactly like the desk used by Mark Twain. An elk print to the left of the cabin's front door is the print that hung above Twain's desk. "He was one of the first guys to write about the West and Americana," Michael explains.

The cabin is small, built just for Michael "to hang out." Even the desk was chosen, in part, for its small size. Of course, the best-laid plans are always open for revision. "When this place got built," he says jokingly, "the entire family decided that they had to be here every weekend. My doghouse became the family vacation home overnight."

Michael thanks his father for bringing him camping at the Red River area when he was a boy. He is knowledgeable about the Native Americans who lived in New Mexico before European settlement. The Comanche Indians came to hunt the area in the spring and summer; Pueblo Indians lived just to the south; Utes were in the area from time to time as well.

Michael also easily explains the story of Spanish land grants to the north - land given by the Spanish king before New Mexico became part of the United States. "The grants are about 400 years old in their tradition," he says. During the 1850s, the government "grabbed" land from descendants of the people originally given the grants. After 200 years, they no longer had their original titles. Some, however, did pass down the titles, and the land still remains in the hands of the great-great-grandchildren of the original settlers.

Red River itself, existed as a goldmining town from 1890 into the 1930s. According to Ken Densow, owner of the Red River Inn, there was never a huge strike like those that made other gold towns more famous, "but they seemed to make a living." Today, Red River welcomes year-round visitors. Winter tourists come for the Red River Ski Area. Spring, summer and fall bring natives from southwestern states seeking respite from the heat. Despite a large tourist population, the town's permanent residents number under 500.

Even diminutive Red River seems clamorous from the perspective of the Murphey cabin, however. It's not a hard thing to understand. The cabin's carefully planned interior offers solace for a writer and a haven away from the world for a family. There is an unreal quality about the quiet within its walls, the sharply-defined mountains, trees and sky outside its doors. The quality, it seems, is simply peace.